A simple method for creating obstacle-to-obstacle ecosystems.

The Adventure Design chapter (p. 123) of the Torchbearer rulebook provides an excellent process for designing an adventure. But let's expand the Ecosystem section (p. 126) and explore ways to build out the connections between obstacles.

Seven-obstacle Design Overview

- Answer the eight Building an Adventure questions (p. 123 - 124)

- Choose seven major obstacles

- Create an obstacle relationship outline

- Add finishing touches to the GM map

Why Seven Obstacles?

Massive 100-area mega-dungeons are not suitable for the game. Smaller dungeons offer more time to delve into detail and give the players meaningful choices. Seven obstacles provide the sweet spot for a three to four session adventure. It doesn't need to be seven obstacles exactly, but keep in mind that less is more.

Most of the time, although not always, a seven-obstacle adventure will also have seven areas. However, there is a significant distinction between obstacles and areas.

Obstacles

An obstacle can be any situation that presents a problem to the party such as orcs guarding the mountain pass, a corrupt lendermann extorting money, or just a rusty lock on a door. At first, the GM describes the obstacle as the group encounters it. Then, the GM gives it a number once a player triggers a test.

Obstacles often prevent the party from proceeding. Physical barriers, like a pile of boulders, are apparent inhibitors, but other obstacles that involve solving, resolving, convincing, engaging with something ephemeral can also obstruct the party in different ways.

A GM can put any number of obstacles in an area, but typically, there is just one major problem per area. Players will spend several turns in an area making multiple tests as they explore. Those preemptive tests usually revolve around the main problem in the area and allow the party to prepare for overcoming the obstacle.

For example, the party encounters a troll in a cavern area. The troll is the "creature problem" for the area, and the party will need to deal with it to continue. The characters try to glean its Nature, sneak back outside the entrance, dig a pitfall trap, and then engage with it to draw it into the trap. After dealing with the troll, the party might search the room, chronicle the lore, examine the bones of its victims, make camp, or any number of other actions that lead to more tests. The troll was the main obstacle for the area, and the party spent several turns on the grind resolving the situation. If the party failed and kept getting twists, they could conceivably spend the entire session in this one area.

Areas

A lot of traditional RPG dungeons use doors as clear demarcations for "rooms," but it is better to think of "areas of a dungeon." In Torchbearer, an area might include a couple of caves, a section of a forest, a suite of rooms in the castle keep, or encompass the adjacent hallways, stairs, closets, nooks, or alcoves of a chamber. A party might clear an "area" of obstacles to reduce danger, find a suitable place to camp, or search for loot or secrets.

Configuration

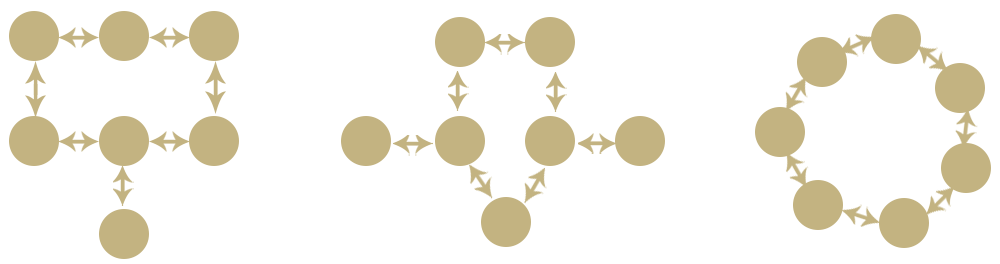

Using techniques from character relationship maps, we can now begin to create connections in a "obstacle relationship outline." The relationship outline plots the seven obstacle points using one of the three configurations. As we begin the outline, we are not thinking about areas or the GM map. We focus on the decisions and choices the party must make and where the obstacles fall within those paths.

The most common configurations of a relationship outline are: branching tree, loop, or hub and spoke. We will use these mental outlines to create tension and build up pressure in the dungeon.

Branch

Branching outlines are ideally suited for Torchbearer because they give the players choices and allow for different ways to explore. The tension between the obstacles can wax and wane as the party follows one branch and then another. A branching distribution of obstacles works well when the party needs to make a pivotal decision to go "this way" or "that way."

Loop

A loop is very similar to a branching configuration, but it makes it easier for the party to engage with all of the obstacles. Situations connected in a loop will often have cyclical themes (e.g., violence begets violence).

Hub

In a hub and spoke paradigm, the outlying spokes connect to a central hub. The hub obstacle should relate to the problems in the spokes.

Ecosystem Relationships

We'll start with a branching outline as an example.

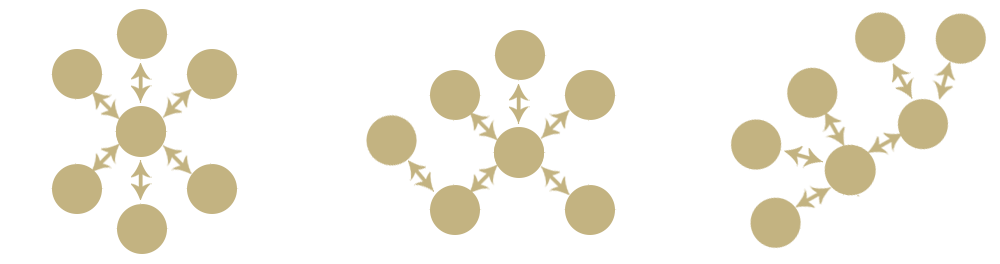

In a hypothetical adventure, a stone spider inhabits the ruins kobold raiders have chosen as their base.

Throughout the adventure, the party can take sides between the spider or the kobolds. Both creatures are preventing the party from looting the ruins, but if the players deal with one or the other, they can get to the good loot buried in the depths. One branch of the outline involves driving away the spider or killing it. The other branch deals with the kobolds' raiding.

We draw a line between each connected obstacle and describe the connection using "because."

The spider eats kobolds because they are easy prey.

Kobolds build defenses against the spider because they don't want to move to a new home.

These motivations, attitudes, and connections create causation. The kobolds are easy pickings for the stone spider. So, to protect their young, the kobolds create a barricade in an attempt to defend against the spider. We can see there is a rivalry and competition between the spider and kobolds.

We want to define the "state" of the dungeon through the connections of these obstacles. One relationship's effect on another obstacle creates an interwoven world. Monsters have very little agency, so they should not be changing things on their own until the characters start altering the ecosystem. The players are the fuel that ignites the smoldering flame - the players are the catalyst of change.

For example, if the party slays the spider but then returns to town, the kobolds might start clearing the rubble, or another creature might move in to fill the void.

Sample Obstacles

Traps

Traps are an environmental problem in a class of their own. Minor traps can abound in a dungeon (traps on locks, chests, doors, hallways, etc.), but there should be at least one major obstacle that is a dangerous trap.

Check out these articles with tips on trap design:

Environmental Problems

Environmental, or physical, problems are the most intuitive of all obstacles because they literally block the party. Use environmental problems to challenge the metaphorical landscape of your dungeon ecosystem. For example, a chasm in the middle of the dungeon could be a symbol representing the schism between two warring orc siblings.

- Climbing up a sheer cliff

- Breaking down a door

- Digging through rubble

- Hopping over giant poisonous mushrooms

- Swimming across an underground river.

- Navigating the catacombs

- Crossing a mountainous chasm

- Sneaking across the broken glass in the tavern

- Moving a heavy boulder

Calamity Problems

Calamities create devastation, a series of disasters, or severe problems for the party. Tragedies are great for raising the stakes and escalating the drama in or around the dungeon.

- Evading a dragon attack

- Escaping a smoke-filled library

- Witnessing an unholy sacrifice

- Fleeing an all-consuming forest fire

- Losing all your treasure gambling

Social Problems

Social problems present the party with opportunities for rich roleplaying experiences while also burning up turns on the grind. Social tests are best when they occur at the point in which the conversation is at an impasse or one side has become querelant.

- Resisting an interrogation by the town watch

- Dealing with a prejudiced the innkeeper that refuses to give you the "job"

- Amusing the noble to save your heads

- Negotiating with the shrewd guild master

- Distributing booty to the pirate allies

Ingenuity Problems

Problems requiring ingenuity do not physically obstruct the party. However, wise groups will take the time to engage with the obstacle so that they are better prepared later on in the dungeon.

- Deciphering the riddle

- Copying the runes

- Banishing the spirit barrier

- Learning the purpose of the burial chamber

- Securing rickety scaffolding

- Weaving a rope bridge out of the giant's hair

- Dispelling the arcane ward

Creature Problems

Creature problems provide an opportunity for considerable risk and reward. Creatures don't always have to be big and intimidating. Creatures like honey bees can present environmental problems and rewards (honeycomb) also. Try to pick at least two different creature types so that you can build the tension between factions, rivals, or competing groups. The creatures are locked in stasis until the players come along to open the floodgates.

- Finding the creature

- Negotiating with the creature

- Questing for the creature

- Fighting with or for the creature

- Spying against the creature

- Sneaking away from the creature

GM's Map: The Finishing Touches

Once we finish defining the relationships of the obstacles, we can move the points around for placement on the GM's map. The benefit is that we've thought through a lot of details in the ecosystem and now have a rich background to inform the dungeon area layout.

The obstacle relationship outline will have a lot more connecting lines than the GM's map, but the framework can inform the geography and topology of the dungeon layout.

Entrances

Having multiple entrances gives the party a chance to strategize. Try to have at least two entries for a seven-obstacle dungeon, although the second entrance should require some work to find or open. It's always good to reward exploration, and adding another way in or out of the dungeon encourages the party to delve into unfamiliar territory. The second door could be a crack in the wall or ceiling, a secret passage, a high-up window, a locked gate, or something that requires some creativity and effort to figure out.

In the spider and kobold adventure, the kobolds would need to create another way out of the dungeon to avoid getting eaten by the spider. Consequently, the kobolds dug a small tunnel back entrance to come and go as they please. This shaft can become another entrance for the party with a little bit of digging or ingenuity, and it adds more detail to our ecosystem.

Secret Areas

As a general suggestion, add one secret area for every five or six areas. Secrets don't have to be rooms though. Hidden passages, niches, knowledge, libraries, alcoves, tombs, or cabinets can reward the party for searching.

Treasure Areas

Loot accumulates in natural locations throughout the dungeon. I recommend scattering 4D of loot per character in the party around the dungeon. The best treasure should be behind the most challenging obstacles.

Rest Area

There should be one area where the party can make a camp and rest. Sometimes this area is right outside the dungeon, while other times, the party will have to secure it. To keep ratcheting up the pressure, camping inside a seven-obstacle dungeon is dangerous. If the party wants a safe space, they'll have to carve it out for themselves.

Complete Example

Step 1 Building an Adventure Questions

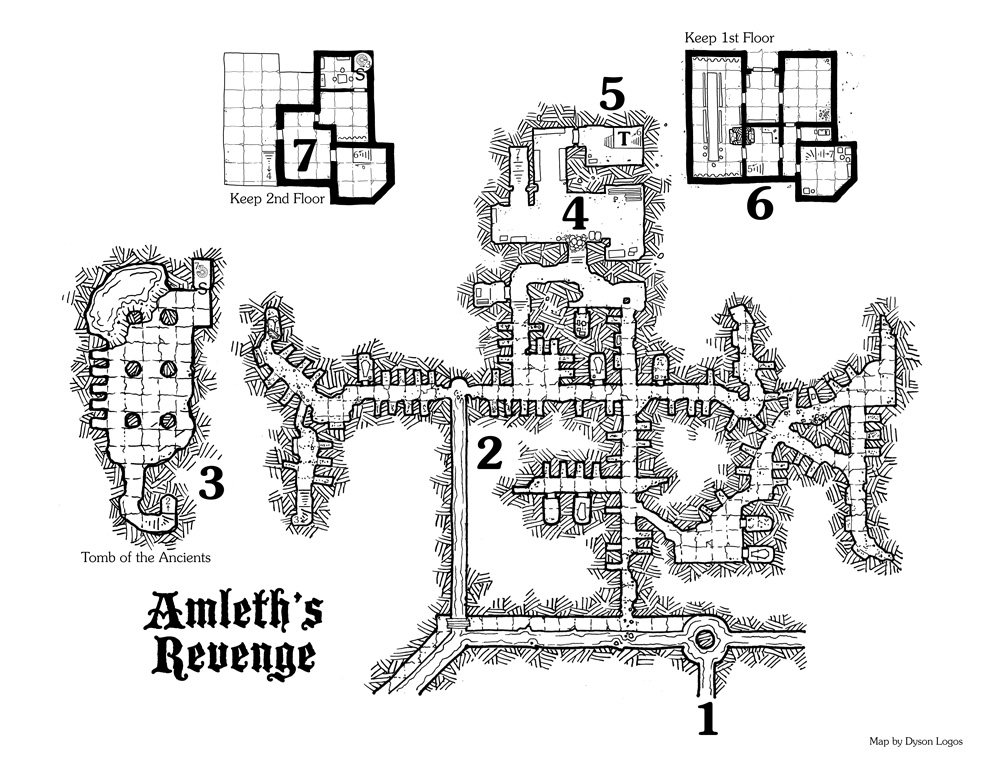

If you have a copy of The Grind, we will use the Amleth's Revenge adventure seed (p. 44) to start our obstacle relationship outline.

Setup

An exiled prince returns home to claim the throne, but his stepfather has made an unholy alliance to maintain power. The prince has laid siege to the castle but cannot capture the castle because the fallen soldiers are raised to add to the stepfather's undead army. The party has a risky opportunity to loot the catacombs or to engage with the factions.

- Adventure Location: Castle catacombs

- Location purpose: Ancestral burial ground

- Treasure to recover: Burial goods and the Chime of the Good Son (magical item)

- Previous inhabitants: Prince Amleth and his father Heimir the Victor

- Current inhabitants: Fengr the step-father, a malicious spirit, a troll, and some undead

- Why not plundered: barricaded and too dangerous

- Alterations: blockades and siege protections

- Traps/features: winding corridors and a collapsing staircase

Step 2 Pick the Seven Obstacles

Creature Problems

- Corpse-fiord troll protecting the Tomb of the Ancients

- Fengr and his retinue raising the dead in the castle keep

Environmental Problems

- Navigating the sewers

- Barricaded hallway in the catacombs

- Winding corridors around the Tomb of the Ancestors

Social Problem

- Amleth's mother questioning Fengr's motives

Trap

- Collapsing stairs leading to the keep

Step 3 Relationship Outline

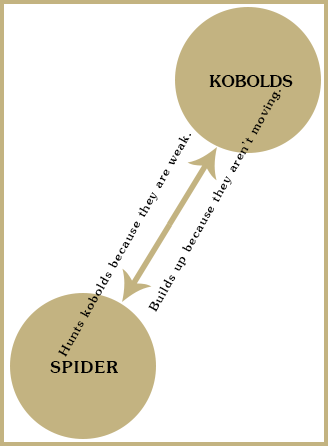

Let's stick with a barricade again. This time, though, we'll use a Hub and spoke design instead of a branching outline. By changing the obstacles and the configuration of the relationships, you can create a completely different adventure using similar elements.

In the spider and kobold scenario, the players don't have to deal with the barricade if they don't pursue the kobold branch. In Amleth's Revenge, there is no avoiding the barricade because it is the main obstacle the party must overcome.

The climatic turning point in the state of the dungeon will be the removal of the barricade. Once the players take down the barricade, the situation in the rest of the dungeon may change through twists or other player actions. The queen, Amleth's mother, feels safe behind the barricade, but she is beginning to question Fengr's motives. The barricade also buys Fengr time to raise the fallen soldiers and send them out to hold the castle's defenses. Also, there is no one guarding the trapped staircase, but it serves as a second line of defense.

Remember, our dungeon is a living, breathing ecosystem. We're not playing a static, unchanging, written-in-stone board game. The GM decides how the consequences of the players' actions impact the state of the dungeon.

When marking your outline, play around with different symbols to convey important points between the relationships. The size of the obstacle might denote the severity of the obstacle.

Step 4 GM Map

Move the obstacle points around in the rough position for the GM's map.

Entrances

There are two ways into the catacombs through Area 1 The Sewers. The party can swim with or against the current. The undead skeletons cannot swim, but they can cross by walking underwater. Going against the current might lead to some twists where skeletal hands grab at the party.

Secret

There is a secret passage between Area 3 that leads to Fengr in Area 7. Fengr uses this passage to consult with the corpse-fiord troll in the tomb.

Loot

Coins and riches are located behind the hub obstacle with the queen in Area 6 and Fengr in Area 7.

Wandering Monsters

Various groups of the undead can appear at any point, and all sorts of environmental twists can keep the party busy.

After we have created our ecosystem, we can connect the dots and draw our map to assemble the catacombs and Fengr's keep.

Download Amleth's Revenge Map PDF

Now we've set the stage, and the game begins.

Grind on,

Koch

Map by Dyson Logos modified by D. Koch